Porn Nostalgia

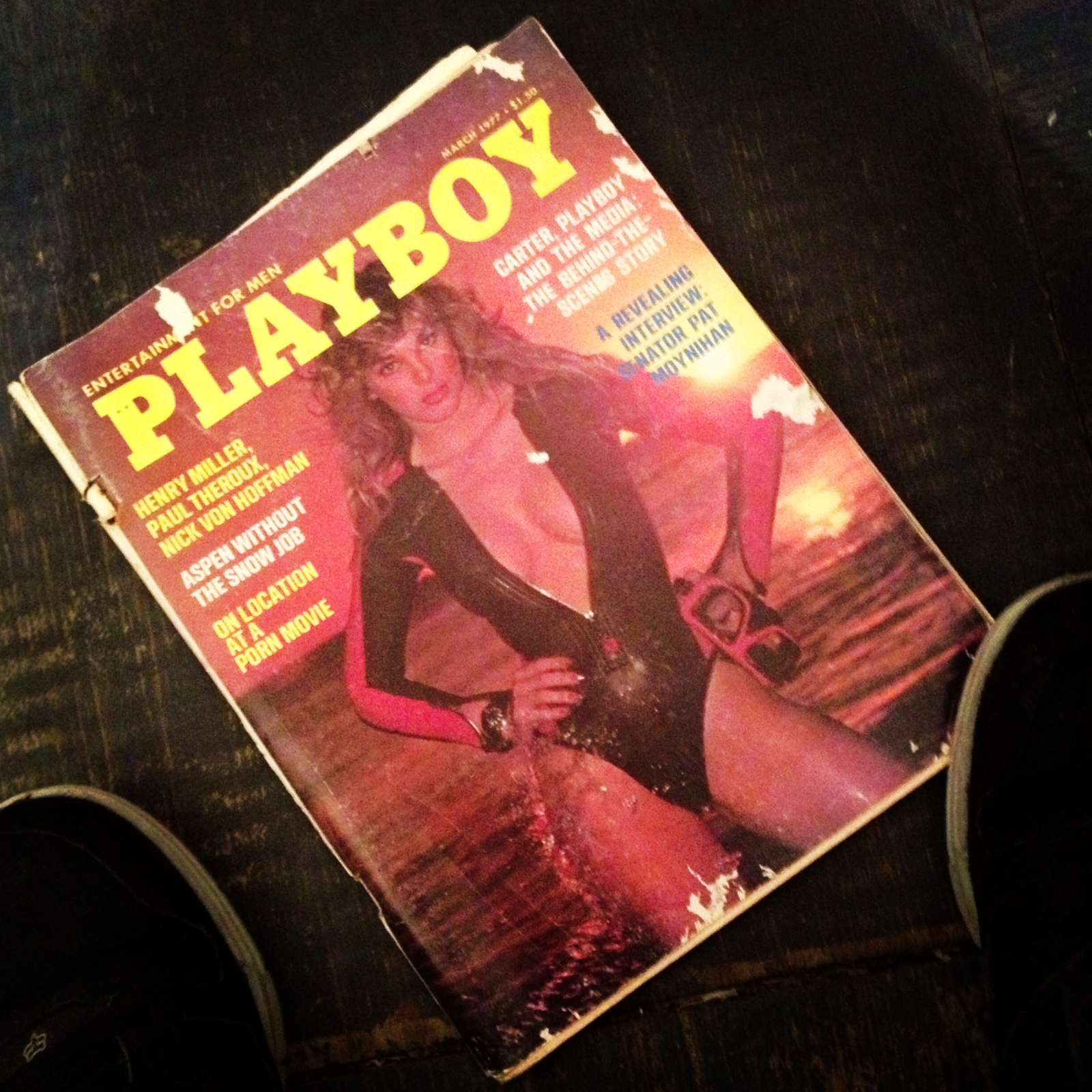

In the ongoing debate about nostalgia's value, I fall pretty decisively on the nostalgia-is-horrible side. In the ongoing debate about the objectification of women, I don't confuse exploitation with empowerment. This isn't a cowardly disclaimer, it is merely a fact I'd like you to have in your head as I defend a 1977 Playboy magazine on the basis of it's nostalgic value.

I'll try and keep it under 10,000 words.

This week my friend and Todcast cohost +Todd DeHart told the story of how oddly well received his tweet of a 1977 copy of Playboy was. His claim was, nostalgia takes the edge off history.

This is a fair and kind of beautiful way to put it. The notion is that it's almost like time travel without consequences. A person goes back in time knowing what he knows now, and the things that were scary or intimidating cease to be. A risque +Playboy spread from 1977 is almost a caricature. It's a way of saying, "How cute. Remember how much of an effort we had to make to see naked women before the Internet?"

I don't want to make you too disappointed, but, sexually, there is nothing new on the Internet. Anything you can stream for $9.99 per day you could purchase a black and white photo of in the 1950s, or see on a grainy 8mm film in a basement, ala Porky's II: The Next Day. The premise was Playboy "legitimized" porn (or at least erotic nudes) by wrapping it in something legitimate.

This is where it gets complicated.

During the 1960s and for a chunk of the 1970s, this fiction was almost true. It's almost still true today. Nearly every writer worth reading over the last half-century published in Playboy. They participate in investigative journalism. Playboy profiled Richard Dawkins less than a year ago, for Christ's sake. But they have an almost disturbing commitment to bare boobs and I cannot understand it. +Playboy provides the kinds of worthwhile reading found in +Esquire, +The Atlantic and +The New Yorker, but also nudes.

Insert "improvement" joke here.

As I said from the start, I was going to make a defense of this in relation to nostalgia, so first, let's get a little nostalgic for Playboy:

This kind of thing was below them 40 years ago, when the magazine aspired to be arbiter of style and sophistication. Playboy proponents (apologists?) argued the sophisticated man of leisure could enjoy the philosophical wit and political insight of its longform journalism, in-depth celebrity interviews and social satire as well as show an almost lofty appreciation for nude women. Women weren't possessed objects, but rather, like the articles in the magazine, ideals. Words were being used to describe truths (if not Truth) throughout Playboy's pages and images to describe beauty, the argument went. And it was a good one on the surface.

There came a point however, where they decided they wanted to compete both with Esquire and with +Larry Flynt and his +Hustler empire. And the story ends with the kinds of ads we see above.

The worthwhile nostalgia is the one where Playboy holds the almost Aristotelean view of leisure. It's a notion that all the good things in life should be actively developed if a man is to achieve balance, which boils down to "It's all good" in today's slang.

The nudes in older Playboy magazines were playing at being art, while today they're playing at being porn. Nostalgia for the pretense of porn as philosophy is bad. But nostalgia for a world where society makes arguments about representations of ideals and their relative value can be forgiven.

Awkward aside: Nostalgia for the word "porn"

When did "porn" became an acceptable modifier meaning "enticing" and "gratuitous?" "Nostalgia Porn" is the objectification of nostalgia for base gratification. I guess the same goes with Food Porn, Travel Porn, etc. It's a shame, really. Not that porn needs to remain very strictly defined—pornography is media aimed at generating sexual excitement (it's not a perfect definition but it's better than the Supreme Court's). But slapping nouns in front of "porn" can only lead down awkward roads. For instance, what would you expect from a link that was tagged "Kitten Porn?"

This blog is based on the Happy Hour Todcast, a news and entertainment podcast highlighting the Eastern Shore. Click here to subscribe on iTunes, or listen below.

I'll try and keep it under 10,000 words.

This week my friend and Todcast cohost +Todd DeHart told the story of how oddly well received his tweet of a 1977 copy of Playboy was. His claim was, nostalgia takes the edge off history.

This is a fair and kind of beautiful way to put it. The notion is that it's almost like time travel without consequences. A person goes back in time knowing what he knows now, and the things that were scary or intimidating cease to be. A risque +Playboy spread from 1977 is almost a caricature. It's a way of saying, "How cute. Remember how much of an effort we had to make to see naked women before the Internet?"

I don't want to make you too disappointed, but, sexually, there is nothing new on the Internet. Anything you can stream for $9.99 per day you could purchase a black and white photo of in the 1950s, or see on a grainy 8mm film in a basement, ala Porky's II: The Next Day. The premise was Playboy "legitimized" porn (or at least erotic nudes) by wrapping it in something legitimate.

This is where it gets complicated.

During the 1960s and for a chunk of the 1970s, this fiction was almost true. It's almost still true today. Nearly every writer worth reading over the last half-century published in Playboy. They participate in investigative journalism. Playboy profiled Richard Dawkins less than a year ago, for Christ's sake. But they have an almost disturbing commitment to bare boobs and I cannot understand it. +Playboy provides the kinds of worthwhile reading found in +Esquire, +The Atlantic and +The New Yorker, but also nudes.

Insert "improvement" joke here.

As I said from the start, I was going to make a defense of this in relation to nostalgia, so first, let's get a little nostalgic for Playboy:

This kind of thing was below them 40 years ago, when the magazine aspired to be arbiter of style and sophistication. Playboy proponents (apologists?) argued the sophisticated man of leisure could enjoy the philosophical wit and political insight of its longform journalism, in-depth celebrity interviews and social satire as well as show an almost lofty appreciation for nude women. Women weren't possessed objects, but rather, like the articles in the magazine, ideals. Words were being used to describe truths (if not Truth) throughout Playboy's pages and images to describe beauty, the argument went. And it was a good one on the surface.

There came a point however, where they decided they wanted to compete both with Esquire and with +Larry Flynt and his +Hustler empire. And the story ends with the kinds of ads we see above.

The worthwhile nostalgia is the one where Playboy holds the almost Aristotelean view of leisure. It's a notion that all the good things in life should be actively developed if a man is to achieve balance, which boils down to "It's all good" in today's slang.

The nudes in older Playboy magazines were playing at being art, while today they're playing at being porn. Nostalgia for the pretense of porn as philosophy is bad. But nostalgia for a world where society makes arguments about representations of ideals and their relative value can be forgiven.

Awkward aside: Nostalgia for the word "porn"

When did "porn" became an acceptable modifier meaning "enticing" and "gratuitous?" "Nostalgia Porn" is the objectification of nostalgia for base gratification. I guess the same goes with Food Porn, Travel Porn, etc. It's a shame, really. Not that porn needs to remain very strictly defined—pornography is media aimed at generating sexual excitement (it's not a perfect definition but it's better than the Supreme Court's). But slapping nouns in front of "porn" can only lead down awkward roads. For instance, what would you expect from a link that was tagged "Kitten Porn?"

This blog is based on the Happy Hour Todcast, a news and entertainment podcast highlighting the Eastern Shore. Click here to subscribe on iTunes, or listen below.

Comments